1. Evolving Software Engineering Paradigms

Imagine you are tasked with updating a decade-old e-commerce platform. The codebase consists of legacy systems, undocumented dependencies, and missing technical context accumulated over years. While reviewing the system, you identify a critical performance bottleneck—a slow database query affecting the checkout process.

A tool like Cursor might suggest an optimized SQL syntax to speed up the query. However, it lacks the ability to diagnose the root cause: a missing index on a frequently joined table, likely caused by an outdated ORM layer. This issue goes beyond simple code completion; it requires strategic thinking, investigation, and a deep understanding of the system’s architecture to resolve.

This distinction highlights the fundamental difference between AI coding assistants like Cursor and GitHub Copilot, which enhance productivity by suggesting code improvements, and AI coding agents like Devin and OpenHands, which aim for higher-level autonomy by reasoning about complex problems, making architectural decisions, and executing solutions with minimal human intervention.

1.1 Software Engineering is not about writing code

The popular perception of software engineering often focuses on coding. However, a Microsoft survey found that developers spend only about 37% of their time on development-heavy activities. A significant 30% is dedicated to communication and planning—activities that require collaboration, requirement gathering, and strategic decision-making.

The Microsoft survey Today was a Good Day, The Daily Life of Software Developers.

The study also found that engineers spend only 3% of their time on dedicated learning. This doesn’t mean learning isn’t important; rather, it suggests that much of the technical skill development occurs incrementally and informally, through debugging, researching solutions, and collaborating with colleagues. As AI coding assistants take on more of the development-heavy tasks, engineers will be freed to focus on continuous learning, problem-solving, and strategic thinking.

This evolution points toward a future dominated by R&D-driven roles. Engineers might spend more time designing novel algorithms for personalized recommendations, architecting systems for handling massive data streams, or developing new security protocols—tasks that require deep expertise and creative problem-solving rather than simply writing code.

1.2 Levels of automation in software development

Fully automating software development remains a challenge due to the fundamental limitations of current Large Language Models (LLMs) in handling long-range dependencies, understanding complex system architectures, and adapting to evolving codebases.

AI-powered coding assistants like Cursor built on top of LLMs enhance the developer experience through carefully designed prompting techniques and innovations that leverage the in-context learning capability of transformers.

This represents the first level of automation, where LLMs handle a significant portion of coding tasks, but human engineers still play an important role in guiding the model. A more advanced stage involves coding agents, aiming for near-complete automation. In this paradigm, the ideal coding agent would handle development autonomously, with engineers primarily reviewing pull requests and monitoring feedback rather than actively writing code.

This shift could fundamentally transform the role of software engineers. Future engineers might concentrate on high-level architecture, system design, and ensuring that AI agents are strategically aligned with business goals.

2. LLM Limitations

Large language models (LLMs) are fundamentally autoregressive systems that predict the next token by modeling the conditional probability distribution, $P(w_t | w_{<t})$ optimized via cross-entropy loss minimization over their training set. While they excel at capturing statistical regularities in human language, their operations are fundamentally distinct from human cognition; they lack grounded world models or causal reasoning frameworks.

To partially bridge this gap, Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting was introduced in 2022. This technique leverages the Transformer’s inherent capacity for in-context learning by explicitly prompting models to generate intermediate reasoning steps. However, depending solely on autoregressive generation, prompt-driven approaches often produce code that, while syntactically correct, falls short on handling complex logical dependencies; this means that we need more context-aware, reasoning-enhanced approaches (Chen et al., 2024).

2.1 The Statelessness Problem

Large Language Models (LLMs) built on the Transformer architecture process text within a fixed-length context window, which serves as a self-contained buffer for input tokens. Unlike human developers, who develop evolving mental models of projects over time, LLMs lack long-term memory, making it difficult for them to anticipate software edge cases or track evolving states in debugging.

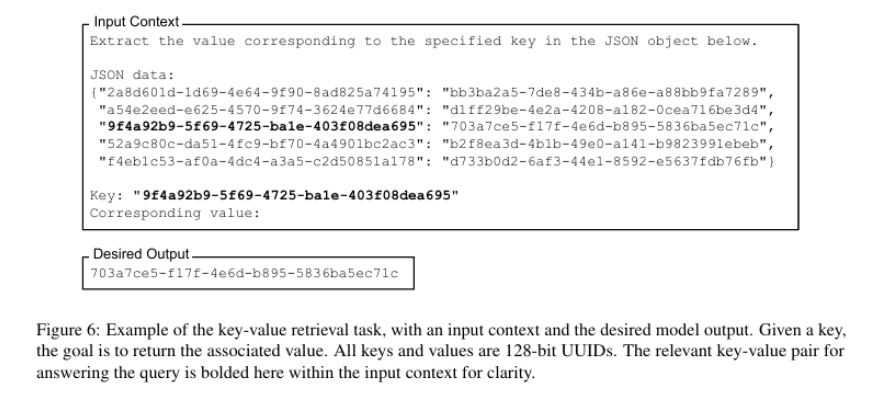

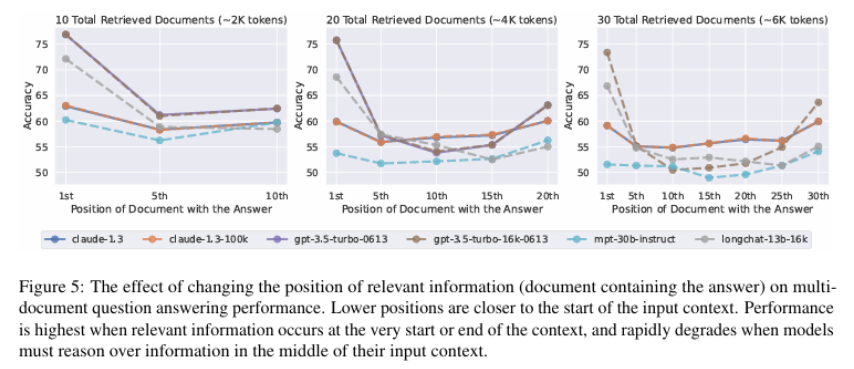

One key limitation arises from their inconsistent ability to retrieve and utilize information embedded in the middle of long input sequences. This phenomenon was highlighted in a study by (Liu et al. 2023), which examined how well models recall specific pieces of information placed at various points within their context window.

A common method for evaluating this behavior is the needle in a haystack (NIAH) test, where a specific piece of information (the “needle”) is inserted at different positions within a prompt (the “haystack”). The model is then asked to retrieve it, revealing how well it retains and utilizes context across different positions. The following figure illustrates an example from Liu et al.’s study:

Snippet from (Liu et al. 2023)

Results from such evaluations often exhibit a U-shaped performance curve. Models are most effective at retrieving information located at the beginning (primacy bias) or end (recency bias) of their input window, while struggling with details positioned in the middle. Primacy bias likely arises because the model’s initial hidden state is strongly influenced by the earliest tokens. Recency bias occurs because the final tokens have the most direct impact on the next-token prediction. This means that crucial information placed in the middle of a long code file or documentation might be effectively “invisible” to the LLM.

Snippet from (Liu et al. 2023)

2.2 The under-representation problem

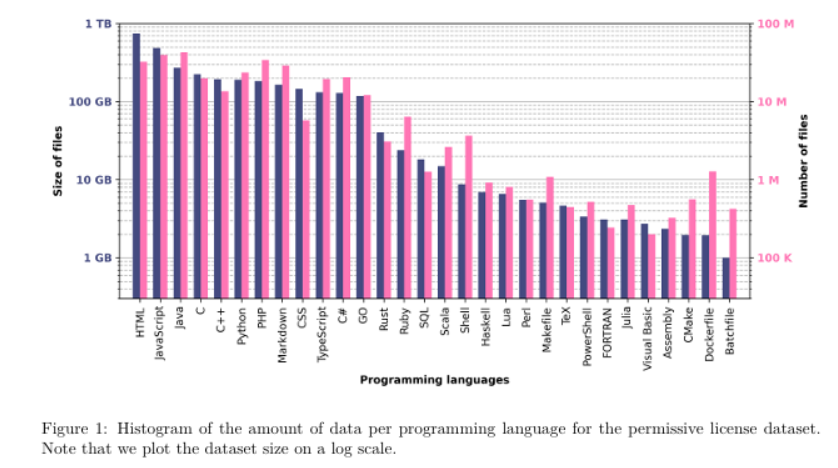

Not all programming languages are equally well supported by LLMs. While models like GPT-4 and Code Llama perform exceptionally well in widely used languages like Python, Java, C, and C++, their capabilities drop significantly for less common languages such as COBOL, MATLAB, or even domain-specific scripting languages like Dockerfile.

Snippet from (Lachaux et al., 2022)

This disparity comes from the distribution of training data. LLMs are typically trained on publicly available code from sources like GitHub, where the majority of repositories are written in a handful of dominant languages. A 2022 study (Lachaux et al., 2022) highlights this imbalance, showing that top programming languages make up the vast majority of the dataset, while others are severely underrepresented. As a result, models struggle with languages that lack sufficient training examples, leading to poor code generation, higher syntax errors, and weaker contextual understanding in those languages.

This issue has real-world implications. In industries relying on legacy systems (e.g., banking, which still uses COBOL extensively), AI coding agents may provide little to no assistance. Similarly, fields requiring highly specialized languages—such as FPGA programming (VHDL, Verilog)—are likely to see weaker AI support unless training datasets become more balanced.

Addressing this challenge requires better dataset curation, including efforts to expand training data with high-quality code from underrepresented languages.

A promising yet challenging approach to addressing the underrepresentation of certain programming languages in training data is the use of synthetic data to generate artificial code samples. However, this method presents a paradox: the very lack of representation in the data makes it difficult to ensure that the synthetic data produced by an LLM is of high quality. If the model has not been sufficiently exposed to the underrepresented language, its ability to generate accurate and reliable code may be compromised.

2.3 The Localization and Navigation Problem

Beyond the inherent limitations of LLMs, AI coding agents face environmental challenges. One crucial challenge is the localization and navigation problem. This refers to the agent’s ability to efficiently find and utilize relevant information within a large, complex codebase. Unlike a human developer who can use tools like IDEs and debuggers.

To better explain the problem, imagine the task of fixing a bug in a specific function not mentioned to the agent.

Identifying the specific files associated with a particular bug—known as the localization problem—is challenging in large projects with thousands of files and complex directory structures. Simple keyword searches often yield irrelevant results due to their reliance on exact term matches and inability to interpret contextual meaning. While semantic search models (e.g., BERT) aim to understand query intent, they’re typically trained on natural language corpora and struggle to parse the syntactic rules, structural dependencies, and formal logic inherent in programming languages. For instance, they may misinterpret API calls or variable scoping, resulting in suboptimal retrieval of code segments relevant to debugging tasks. Recent code-specific models (e.g., CodeBERT) attempt to bridge this gap but underscore the persistent need for domain-aware search solutions.

Without efficient localization and navigation capabilities, the agent might waste computational resources analysing irrelevant code, fail to identify the root cause of a problem, or introduce new bugs by making changes without understanding their broader impact. This problem is exacerbated by the statelessness of LLMs, as discussed earlier.

3. Current Approaches and Architectures

3.1 Early Specialized Agents (SWE-Agent)

This agent is designed to solve real-world GitHub issues. It uses a specialized “Agent-Computer Interface” to interact with a file editor and command-line terminal. This allows for more natural navigation and manipulation of the codebase. By providing a structured way to interact with files and directories, it effectively addresses the problem of locating specific code elements (Yang et al., 2024).

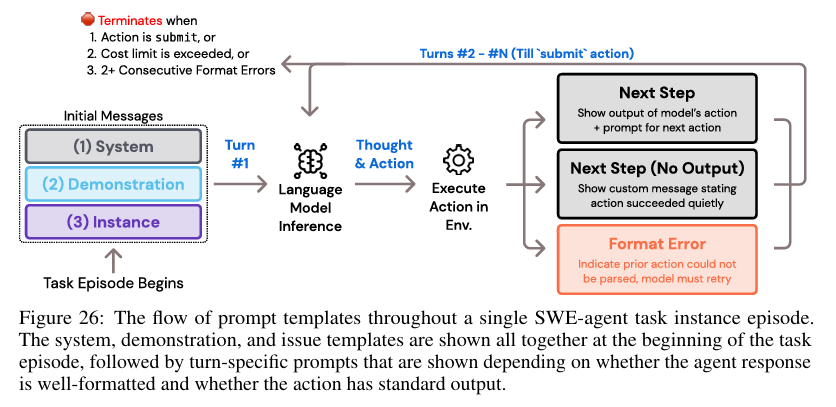

This agent can be classified as a ReAct agent (Yao et al., 2022). It performs actions within a defined set of tools and commands, such as navigating repositories, searching files, viewing files, and editing lines. After each action, the agent observes the resulting changes in the computer environment, which includes a terminal and a file system.

Snippet from (Yang et al., 2024)

This architecture implements key requirements for building coding agents. The agent uses clear prompts, error messages, and history processing to maintain a concise and relevant context. It also condenses older observations, reducing the number of tokens and eliminating irrelevant information. This prevents overly long input prompts for the language model (LLM).

Following the ReAct architecture, this agent generates both a thought and a command. It then incorporates feedback from the command’s execution within the environment. While this is not a comprehensive planning system, this approach allows for localized decision-making, focusing on the next best action rather than attempting to create a full, complex plan, which can be challenging for LLMs.

Snippet from (Yang et al., 2024)

The agent’s performance is measured using various benchmarks and metrics, primarily the Pass@1 benchmark. This metric represents the percentage of instances where all tests pass successfully after the agent’s generated patch is applied to the repository. Using GPT-4 Turbo, the agent achieves a 12.47% success rate on the full SWE-bench test set and 18.00% on the Lite split.

However, using a ReAct-based architecture for coding agents has drawbacks, notably the cost of operation. These agents address complex problems through a sequence of tool usage, observation, and repeated cycles. This process requires multiple calls for each sub-task, leading to significant token consumption. Furthermore, an initial incorrect decision can trigger a cascade of subsequent errors. These errors can potentially lead to infinite loops, where the agent repeatedly performs the same actions without making progress.

3.2 Unified Action Space Agents (CodeAct Agent)

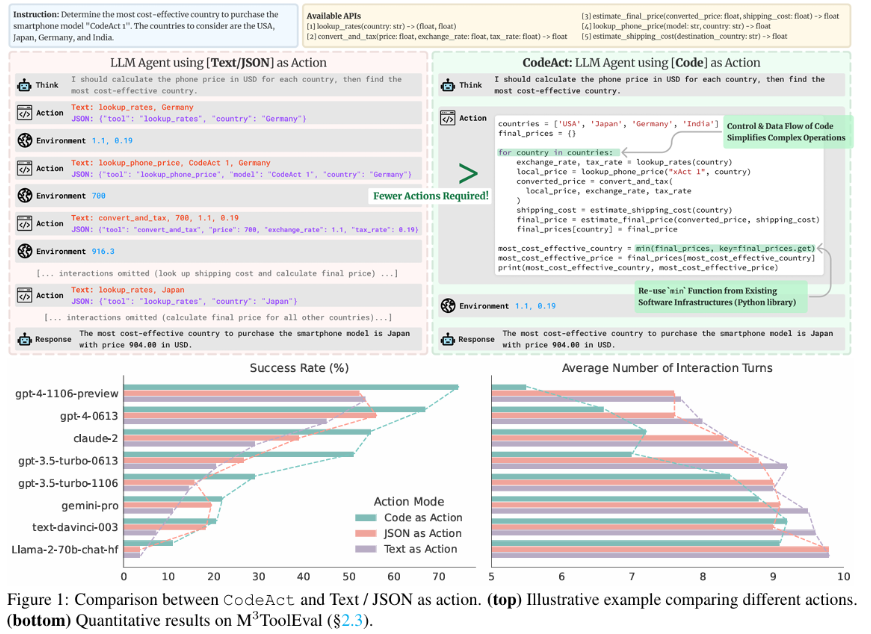

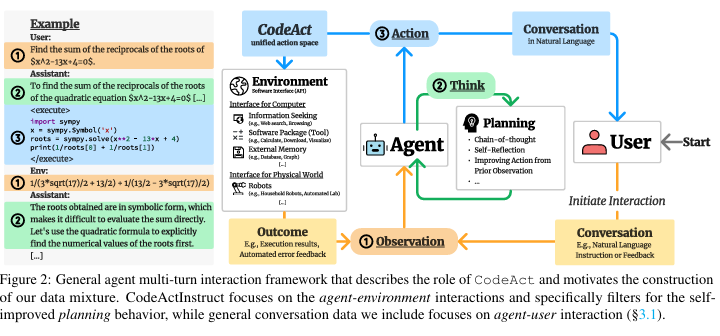

The CodeAct agent (Wang et al., 2024) employs a distinct problem-solving strategy by generating executable Python code as its actions. This method capitalizes on the LLM’s coding abilities, enabling it to interact with the environment through code execution and feedback. This approach allows CodeAct to consolidate all agent-environment interactions into code, resulting in a much broader action space compared to the SWE-Agent.

Snippet from (Wang et al., 2024)

This architecture is designed for multi-turn interactions. It allows for dynamic adjustments to actions based on observations, such as code execution results. This facilitates iterative refinement and adaptation during problem-solving.

Snippet from (Wang et al., 2024)

CodeAct differs significantly from the SWE-Agent. It relies heavily on the ability to generate accurate and robust Python code. This may require further instruction fine-tuning to improve performance. Datasets like CodeActInstruct have been developed, focusing on agent-environment interactions and self-debugging. Fine-tuned models, such as CodeActAgent, can directly interact with Python interpreters and open-source toolkits, reducing the effort needed for action parsing and tool creation.

For closed-source models, CodeAct agent outperforms the SWE-Agent on the M3ToolEval benchmark using the same model (GPT-4 Turbo), achieving a success rate of 74.4% compared to 18.00%. This demonstrates the effectiveness of code execution as an action in coding agents. However, this architecture relies on strong coding capabilities within the LLM. As observed in the study, the best open-source model achieved a 13.4% success rate on M3ToolEval, while the best closed-source model, gpt-4-1106-preview, reached 74.4%. This highlights the significant performance gap based on the LLM’s inherent coding abilities.

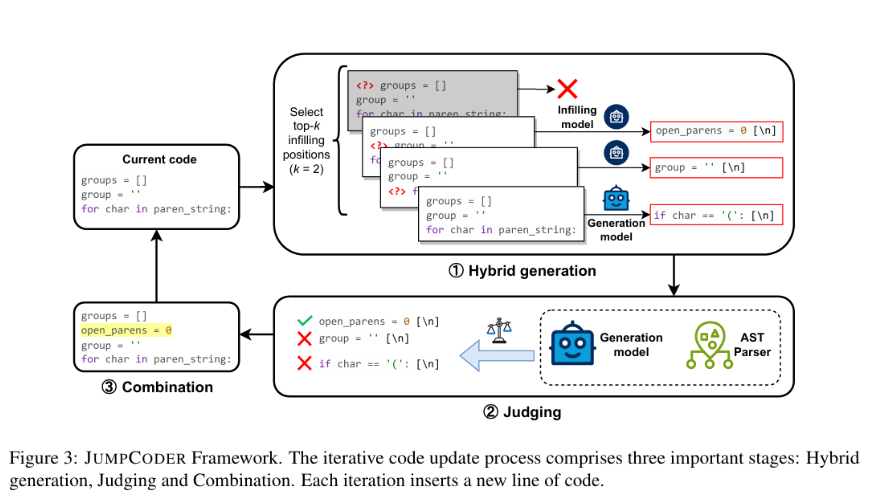

3.3 Non-Sequential Generation (JumpCoder)

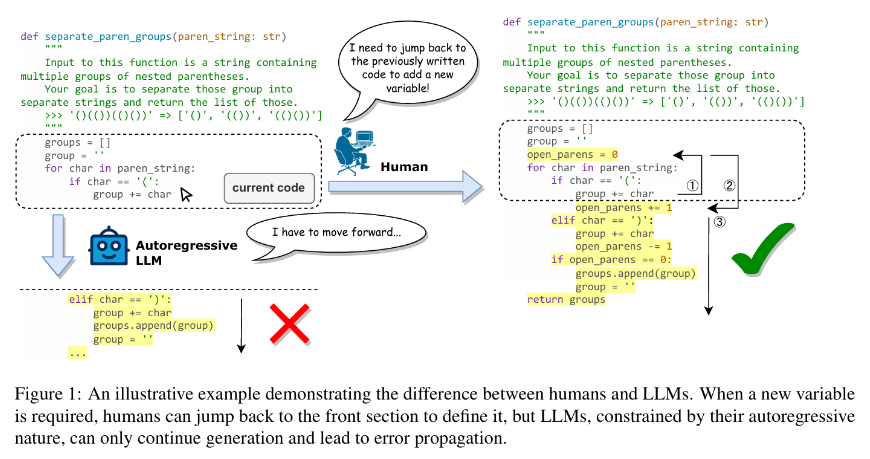

The autoregressive nature of transformers, which involves predicting the next token sequentially, presents challenges for code generation. Coding is not merely a next-token prediction task but rather an iterative process of modifying existing code to add features or alter behaviour. JUMPCODER (Chen et al., 2024) addresses the irreversibility limitation of large language models in code generation, adopting an infill-first, judge-later approach.

Snippet from (Chen et al., 2024)

This is achieved through an online modification technique that inserts new code into previously generated code. This allows the model to add missing statements or correct errors. After the generation of each line, the model experiments with filling at the k most critical positions following the generation of each line.

The model identifies the most uncertain parts of the current code by quantifying uncertainty using the logit value for the initial non-indent token, with lower logit values indicating a higher potential for improvement through the insertion of new code.

After infilling, the modification is judged using both an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) parser and Generation Model Scoring. The AST parser enables a deterministic assessment of the infill’s correctness, particularly when the code uses undefined identifiers, providing a clear yes/no answer to whether the infill resolves potential issues. Generation Model Scoring assesses the overall generation quality to determine the potential impact of infills.

Snippet from (Chen et al., 2024)

The results consistently showed that JUMPCODER enhances performance across different software engineering benchmarks across different programming languages.

4. Future Directions

While the presented architectures have created new ways of using LLMs to generate code. These solutions are just workarounds around the root problems of these models. AI coding agents must overcome current limitations and embrace new paradigms to reach their full potential.

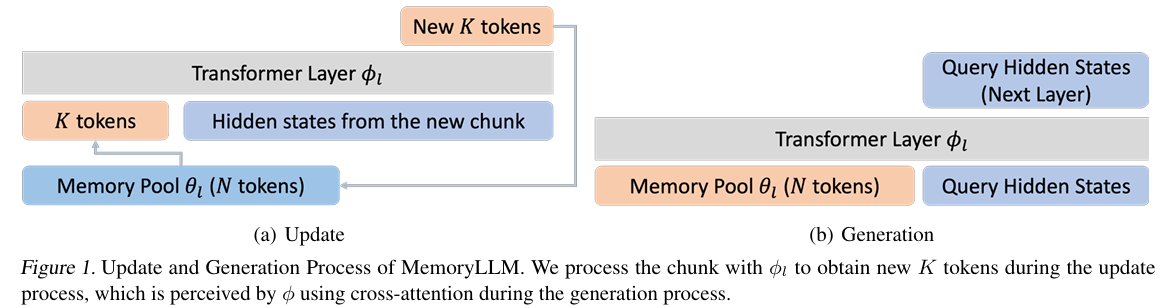

4.1 Enhanced contextual understanding

To truly understand and manipulate code like a human developer, agents need to move beyond the constraints of fixed-length context windows. This necessitates the integration of long-term memory, enabling systems to retain information from past debugging sessions, architectural decisions, and coding patterns across multiple projects. Such persistent memory allows the agent to build an evolving mental model of the codebase.

Recent advancements in AI research have explored models with enhanced memory capabilities. For instance, the M+ model integrates a long-term memory mechanism with a co-trained retriever, dynamically retrieving relevant information during text generation, thereby significantly enhancing long-term information retention (Wang et al., 2025).

Snippet from (Wang et al., 2025)

This suggest also employing hierarchical representations of code, such as graph-based models that map out dependencies at various levels of abstraction (module, class, function), will enable smarter context-aware navigation. This enables the agent to zoom at the right part an approach similar to what JUMPCODER system done when deciding where to infill.

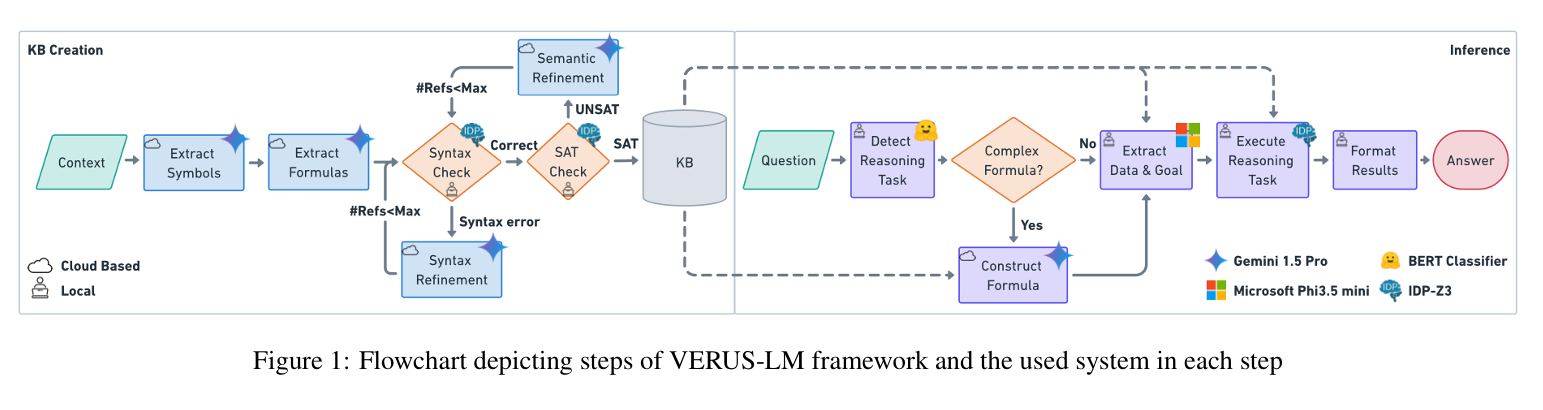

4.2 Advanced Reasoning and Decision-Making

To advance AI coding agents beyond statistical pattern matching, integrating sophisticated reasoning capabilities is essential. One promising approach involves combining Large Language Models (LLMs) with symbolic reasoning. The VERUS-LM framework exemplifies this by merging LLMs’ semantic understanding with symbolic solvers to enhance complex reasoning tasks (Callewaert et al., 2025).

Snippet from (Callewaert et al., 2025)

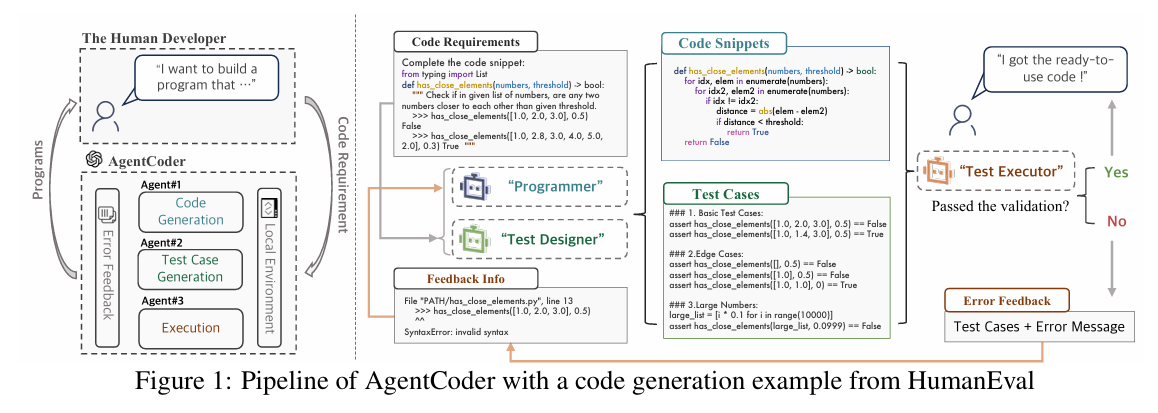

Another active research area focuses on collaborative multi-agent frameworks to improve decision-making and reliability. AgentCoder introduces a multi-agent system where specialized agents—such as a programmer agent, a test designer agent, and a test executor agent—collaborate iteratively to generate, test, and optimize code, thereby enhancing overall code quality (Huang et al., 2023).

Snippet from (Huang et al., 2023)

](https://med-karim-ben-boubaker.github.io/covers/cover-ai-coding-agents.jpg)